My brother and I were never truly opposites. I was no Apollo to his Dionysius. Even so, it was my own Apollonian voice I would hear saying — as he climbed to the top of the chimney or peered into the apple crate full of fireworks he’d just lit — “Chris, no.”

When Christopher was 14 and I was 8, he learned to jump into the swimming pool from the second-story window of our house. It was no direct, vertical descent mind you. To reach the safety of the pool, he had first to clear several feet of roof overhang and then successfully sail over a flagstone patio. Yet, as he tumbled out into space and then a few breathless moments later entered the water with a huge splash, I remember how his eyes sparkled with exuberance and adrenaline. Once I tried jumping, but my descent was exuberance-free. Eyes clenched tight, I just wished it over. Naturally, I entirely missed the point, but of course I didn’t realise that at the time. For Chris, jumping gave him a few moments of bliss; he was in his own element shooting through outer space like a meteorite — exuberantly burning up.

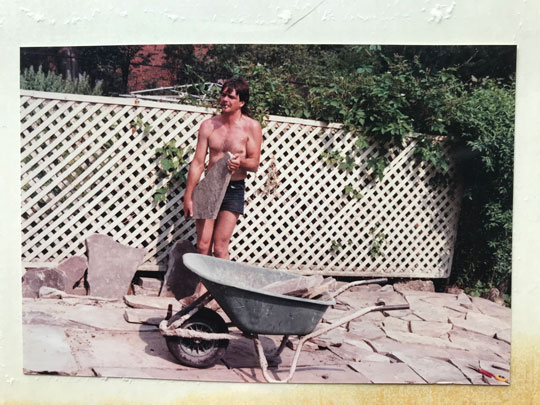

Of course we all said that he’d burn out early – his thirst for adventure would one day be his downfall. That thirst would later morph into a thirst for sugar (something he never lost even after every tooth rotted out of his silly head), then a thirst for drugs (the scourge of my late childhood when his drug induced rampages terrorized the family). So, not only did my formative years convince me that my role was to beware of danger, it somehow became embedded in me that risk was a thing to be avoided. After all, I was the thoughtful one, the careful one, the “good boy”.

And so we became different in every way possible. Even our musical tastes diverged. While he followed Janis Joplin, I committed myself to Mozart and set out be a classical musician. Classical music may seem to fit the staid and safe narrative of this story, but I do distinctly remember the night the orchestra played Tchaikovsky’s Francesca Da Rimini Overture with such fury that something in me snapped. I let go of trying to play and just let go into being the music. For a few spectacular moments I became suspended high above the frantic orchestra gazing down at my own frenzied fingers doing what they’d trained themselves to do. In the wild rush of the music all around me, I became invincible and, like my thrill-seeking brother, I suddenly found myself playing purely for the thrill of the ride; riding that same adrenaline rush he so craved.

As Christopher aged, he did eventually quiet down, and he didn’t die young as was predicted, and not in some thrilling explosive demise as was also conjectured. He passed away quietly at the hospice he’d checked into. To wait for his turn. On that last, sunny autumn afternoon at the hospice — his last day still tethered to planet Earth — I wonder if he hoped that death, when it came, would maybe present itself like one of those adrenaline rushes he once craved. I hope so.

When my time comes, God help me if all I can think of is how to stay safe, how to lessen the impact, how to manage everything. If that happens, I’ll for sure have missed the point. Maybe it’s time I seize onto the feeling of what it’s like to be that alive. Like I’m free-falling in space many miles above a distant blue swimming pool. Imagine if all I can think is, “Man, what a rush this is!”